The Icelandic Settlement of Markland

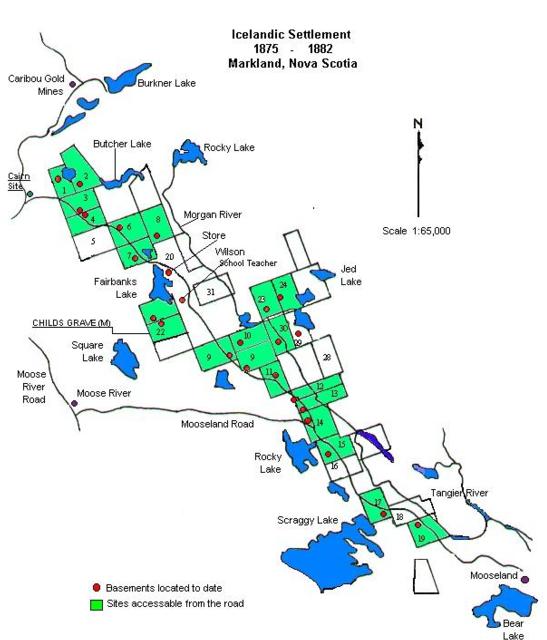

After the confederation of Canada in 1867, the Dominion Government in Ottawa and the Government of Nova Scotia undertook immigration programs to attract settlers to Nova Scotia. John Anderson, an immigration agent who was living in Halifax but was originally from Iceland was hired by the Government of Nova Scotia to attract Icelandic settlers to the province. James Van Buskirk, Deputy Crown Surveyor, was commissioned to explore the interior lands in the Musquodoboit area for immigration purposes. Gold had been discovered around the year 1858 in the Mooseland-Tangier area. To the north was the village of Caribou Gold Mines where prospecting had begun in 1867. Gold had also been discovered at Moose River Gold Mines in 1866. As these communities needed supplies of food and labourers, it was ideal to put a settlement of farmers and work hands near these villages.

Influenced by Van Buskirk's recommendation of the area, the Government of Nova Scotia instructed the Commissioner of Crown Lands to lay off in 100 acre lots, over 3000 acres of land in the area now known as Markland. A term and condition to obtain a Crown Grant to the 100 acre blocks of land required settlers to remain for a period of 5 years and to clear up to 10 acres of land. The head of each family was granted 100 acres of land and was allowed to choose their site. The government provided a log dwelling, a wood stove, an axe and a hoe and supplies for 1 year. John G. Higgins, local carpenter was commissioned by the Province to build log houses for the settlers.

In the spring of 1875, 19 Icelandic families (80 persons) arrived in Nova Scotia from the failed settlement in Kinmount, Ontario. Between the fall of 1875 and 1879, 13 more families arrived, some directly from Iceland. The total population in 1880 was 200. Employment was given to the newly arrived settlers to build a road from Tangier to Musquodoboit through the settlement at less than $2.00 a day. Some of the men found employment in the nearby gold mines.

Following the Icelandic tradition, farms were named after the features of the surrounding landscape; for example, Árbakki was a homestead located by the brook. In 1878, one of the settlers, Jón Rögnvaldsson prepared a survey of the Icelandic farms in Markland which was updated in 1879. The 1881 provincial census provides the names of the families and the other persons living in each household. The government built a school for the settlers and hired a teacher, Alexander Wilson, a Scotsman. The settlers were Lutheran in religion and 100 acres of land was granted to the Lutheran church but a church was never built. In the second year of the colony Reverend Charles Cossman and Reverend Luther Roth from Lunenburg came to the settlement to conduct services, baptize children and hold communion. They also performed marriages and funerals. These services were held in the school building, which also served as the community center.

Life was difficult in the settlement. The land was hilly and densely wooded. Between the hills were large stretches of bog. The soil was rocky and shallow, unsuitable for farming. Despite these conditions the community prospered for several years. Most of the settlers came to possess some livestock such as 2 cows, a few sheep and a pig. There was a yoke of oxen in the community which was shared for land clearing. All the settlers grew wheat, barley and potatoes but realized each year that they could never prosper in this barren and unfertile place. Their back breaking work would never pay off. There was always a lively correspondence going on between the Icelandic communities in the west. Promises of a better life were held out to the other settlers in Gimli, Manitoba, North Dakota and Minnesota. From 1881 to 1883 most Markland families sold their lots and left. However, a few remained whose descendants are still here in Nova Scotia. In 1884 a statute was passed by the Government of Nova Scotia to escheat to the Crown those lands set aside for the Icelandic settlers, because they had departed. In the 1930s the remains of the log dwellings were still visible in the Markland settlement. Eventually the houses collapsed and logging operations were carried on throughout the site. The foundations exist today as a reminder of the short-lived settlement.

As a millennium project, the Icelandic Memorial Society of Nova Scotia erected a memorial cairn at the entrance to the settlement. A special dedication ceremony was held with guests and dignitaries from Iceland, Canada and the USA. With consent of present day landowners in Markland, pathways have been cleared and family farms marked. A replica of an Icelandic log cabin has been constructed on Staðartunga, the lot where the first child was born in Markland. The Society continues to research family histories of Markland and the endeavor to find descendants remains an important goal.